Large pieces of paper with brightly colored dots and occasional scribbles covered the walls. People walked slowly around the room, absorbed in the displays. Two or three individuals clustered together, talking and gesturing.

The setting could have been a modern art exhibit, but in fact it was a conference room at Shoreline City Hall, where staff were screening strategies to reduce community use of fossil fuels. The dots and notes contained staff commentary on the city’s readiness to tackle specific initiatives, and the barriers they need to overcome.

The findings, which the Shoreline City Council heard on October 13, are organized according to what the city agencies can do on their own, what involves regional partnerships (such as the King County-Cities Climate Collaboration), and what requires state advocacy.

These events are the latest steps in a year-long effort to set the city on the road to dramatic carbon reduction. In 2013, the Shoreline City Council adopted bold goals to cut community-wide carbon emissions in half by 2030, and shrink them to 80 percent below 2007 levels by mid-century. The Shoreline Climate Action Plan had outlined efforts that would begin to make reductions in the areas of energy and water conservation, materials and waste management, transportation, and urban greenery.

The missing piece was figuring out which of the possible actions would make the greatest difference in reaching those goals, leading Shoreline to ask Climate Solutions’ New Energy Cities program to provide analysis and guidance on which strategies to pursue first.

Mapping Energy and Carbon Reduction Pathways

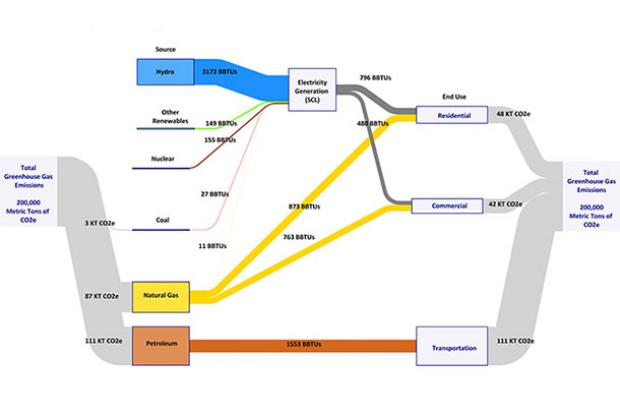

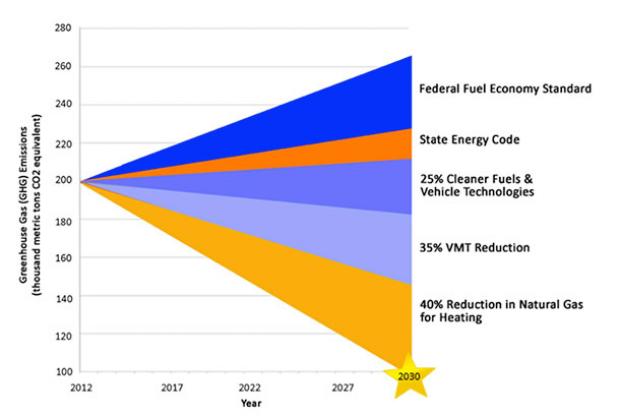

In early 2014, New Energy Cities created an energy map and a carbon wedge analysis to depict what it would take to meet the 2030 goal.

One immediate insight was that the community was farther along the path to being carbon-neutral than other suburban cities because Shoreline’s electricity comes from Seattle City Light’s ultra-low-carbon supply. Therefore, the community needed to focus on reducing petroleum use in cars and natural gas use in buildings in order to meet its carbon reduction goals.

Based on this analysis and additional staff input, New Energy Cities recommended three broad carbon reduction targets and a package of potential strategies associated with each:

- 35 percent reduction in passenger vehicle miles traveled;

- 25 percent reduction in the fuel carbon intensity of passenger vehicles; and

- 40 percent reduction in natural gas use for heating in existing buildings.

Meeting these targets will be a heavy lift, but the strategies to achieve them are known.

Strategies for City Carbon Reduction

In transportation, some of this work is already underway. The city is planning for two Sound Transit light rail stations in 2023, with changes in development rules to accommodate future growth and redevelopment. The Shoreline City Council has also unanimously supported Gov. Jay Inslee’s proposal for a statewide Clean Fuels Standard.

But the need to make dramatic reductions in transportation carbon prompted New Energy Cities to propose other concepts, ranging from policies that put a price on traveling in a single-occupancy vehicle to building codes that pave the way for wider use of electric vehicles (EVs).

Among the most effective strategies, statewide carbon pricing and promoting electric vehicles are likely to find more support than transportation congestion pricing, which Seattle consultant Nelson\Nygaard called “the most essential strategy over the long term, as it offers the benefit of substantial direct VMT and [carbon] reduction.” Congestion pricing could be a hard sell in a growing suburban community.

Reducing natural gas consumption will be also challenging, as many homeowners have recently opted for cheaper natural gas over electric resistance heating. But carbon math and common sense dictate that the use of all fossil fuel, including natural gas, must decrease dramatically if Shoreline is to meet its climate goals.

Partnering with community energy efficiency programs to insulate existing buildings and install electric heat pumps will be critical, as will support for a stricter state energy code that requires deeper energy efficiency in new construction.

Statewide carbon pricing would make most of these solutions easier to implement, by strengthening their business case and potentially representing revenue for local programs. But on-the-ground urban strategies remain essential with or without carbon pricing, as they are the bricks-and-mortar pathways to a low-carbon future.

Shoreline’s blend of art and science is working well so far, in large part because Shoreline’s mayor and city council have expressed a clear and unanimous commitment to climate action, and lead staff have the expertise to organize a complex process involving multiple agencies. The road ahead is a long one, but Shoreline’s staff and decision-makers now have a sense of where to start, where they are headed, and what the mileposts are along the way.