Microsoft’s campus in Redmond, WA is effectively a city of 500 acres and more than 125 buildings, with a daytime population of 58,000. This urban hub is also a pioneer in building energy management, saving an estimated $1 million a year in energy costs.

Now a small team of Microsoft engineers are poised to revolutionize energy management for real cities across the world, and King County, WA is the largest U.S. local government to adopt their model.

Partnering with MacDonald-Miller, ICONICS, and Microsoft, King County has launched an energy-smart buildings project to address King County Executive Dow Constantine’s priorities of climate action and good government.

MacDonald-Miller will install ICONICS software free of cost using Microsoft’s cloud-based platform at the Ryerson Transit Base, Bow Lake Recycling and Transfer Station, Brightwater Center, East Transit Base, and Chinook Building. Without adding new meters or sensors, the software will draw from existing data sources to show facility managers where they are wasting energy, why, and what to fix.

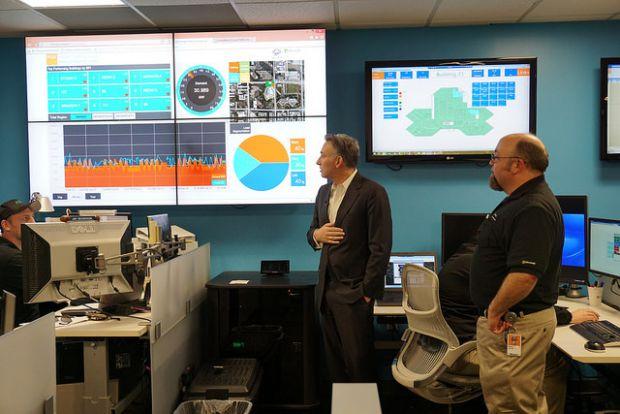

Executive Constantine announced the pilot on February 25 at Microsoft’s Redmond Operations Center (ROC), also known as the Energy-Smart Buildings Lab.

“My commitment to creating the best-run government in the United States includes taking advantage of emerging technology that makes our operations more efficient,” said Constantine. “This innovative partnership will reduce our energy consumption, our electricity bills, and our carbon emissions, all at no cost to local taxpayers.”

Darrell Smith, Microsoft Director of Facilities and Energy, has championed the Microsoft initiative since its inception.

“Facilities management is a reactive business, but it doesn’t have to be that way,” Smith told a group of elected officials touring the Microsoft project. “We used to walk around with paper orders and clipboards, taking weeks of data crunching for a building snapshot that was 60 to 90 days in arrears.”

Smith noted that energy spikes stand out on the easy-to-read dashboards, making for fast detection compared to the past practice of engineers combing through spreadsheets of data. This functionality has transformed the team’s work from a needle-in-a-haystack approach to a sophisticated building energy management system.

Demonstrating the software’s power, Microsoft ROC Manager Tearle Whitson called out to one of the six Microsoft employees working at computer stations in a room of colorful dashboards, “Toggle to the floor level map that shows occupant comfort.” The screen displayed a floor plan of an office building, with temperatures represented as different colors, and then a second layer of information to pinpoint potential mechanical problems.

The system’s financial benefits are immediately obvious. Dragging his mouse across a display screen, Smith sorted a list of building operations problems, or “faults,” by most to least wasteful, quickly identifying a solution to a fault that could “save $22,000 in 30 seconds.” In the old system, only an eagle-eyed building analyst reviewing utility spreadsheets would have caught the fault.

Staffing is easier, too.

“One to two mechanical engineers used to spend two weeks on generating building reports, visiting only 20 percent of the campus in one year. We had mondo spreadsheets to go through, and we wouldn’t return to the same building in five years,” Smith observed. “Even after the building tune-up, the operator could have thrown something out of whack inadvertently. Now we have real-time data campus-wide, and we’ve started monitoring our campuses across North America.”

If applied in public and private buildings countywide, this type of software could help achieve at least three of the joint commitments of the King County-Cities Climate Collaboration: reducing carbon emissions in government operations, adopting and implementing building energy disclosure policies, and ultimately achieving net zero carbon emissions in all new buildings by 2030.

The software would provide an ongoing, real-time view of how buildings perform against design expectations, and how occupant behavior contributes to energy use. This approach also demonstrates how building owners and managers could meet proposed state legislation (HB 1278), which would require annual reports of building energy performance.

Elected officials from the K4C member cities of Bellevue, Kirkland, Issaquah, and Sammamish attended the King County project launch to consider how similar systems could be applied in their cities. Such innovation will be critical to achieve King County’s community-wide goal of halving carbon by 2030.