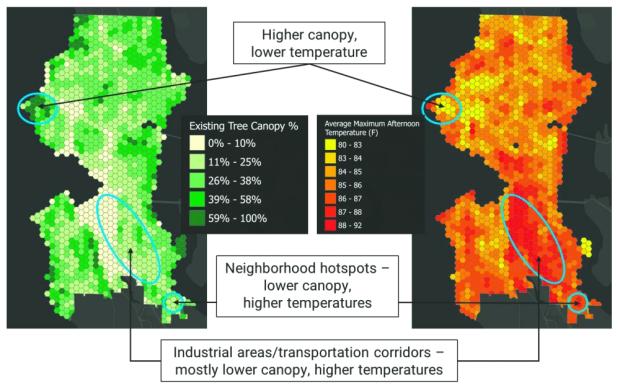

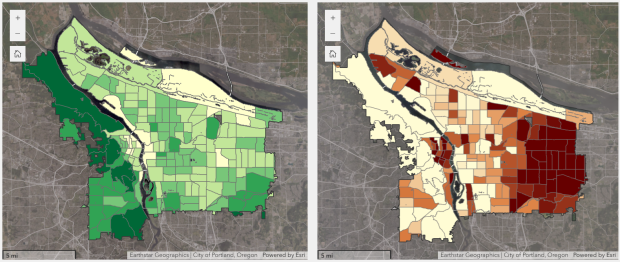

Heat Island sounds like the title of a bad reality TV series, but it’s the lived reality for too many city dwellers during heat waves. The reality was particularly brutal for the 69 Multnomah County residents who died as a result of the “heat dome” event in the summer of 2021. At the height of that heat wave, researchers from Portland State University recorded an air temperature of 124° in a parking lot in Lents (the hottest neighborhood in Portland). Meanwhile, the thermometer read 99° in a more heavily forested neighborhood in northwest Portland. For residents of these neighborhoods, that 25° was the difference between balmy and blistering (especially for those without cooling in their homes), and the lack of natural shade played a surprisingly large role.

What is an urban heat island?

A phenomenon called an urban heat island affects Portland's Lents neighborhood and other highly urbanized regions. Affected areas have abundant human-made buildings and pavement but few trees or other green spaces (primarily dense urban neighborhoods). On hot days, buildings and pavement absorb and retain more heat than trees and foliage would. As a result, dense urban areas experience higher average temperatures and cool off more slowly than surrounding rural areas. This effect is magnified by higher ambient temperatures and the degree to which shade-providing trees and other greenery are absent in an area. Urban heat islands and their negative effects persist throughout the Northwest, across the country, and worldwide.

To clarify, the urban heat island phenomenon is not caused by climate change. However, the effects of climate change are worsening the urban heat island effect, making cities run hotter.

The great benefits — and high price — of shade

Urban heat islands are caused by too many buildings and not enough green space. Accordingly, a natural solution is to add greenery back into cities.

Trees are incredibly important in the wilderness and the urban jungle. In both environments, they provide shelter from the sun on the hottest summer days, absorb the climate pollutant carbon dioxide while releasing oxygen, support biodiversity, and reduce the severity of flooding by controlling runoff. Natural shade in public spaces also improves a community’s quality of life by encouraging neighbors to interact and promoting walkability and the use of active transportation, among other benefits.

However, it’s never as simple as just planting trees. Urban green spaces cost money to construct and maintain. They also require cooperation between policymakers, urban planners, landowners, non-governmental organizations, and community members to succeed. Local tree cover issues are often complex and controversial, involving building codes, land use planning, and the tension between protecting existing trees and planting new ones. Additionally, the ongoing care of trees must be planned for and budgeted.

Major thoroughfares running through Portland’s Lents (top) and Laurelhurst (bottom) neighborhoods. Note the distinct differences in tree canopy.

Images courtesy of Google Maps Street View.

SHADE: Coming soon to a city near you?

Thankfully, a bevy of federal and state investments have become available to grow and support more urban forests. Washington’s Climate Commitment Act (CCA) includes $5.9 million for improving urban tree canopies, prioritizing communities overburdened by air pollution and other environmental health impacts. This funding bolsters the Evergreen Communities Act, passed in 2008 and revitalized in 2021. Nonprofits like The Nature Conservancy and Friends of Trees have long supported the growth of urban tree canopies. Local efforts to grow and equitably distribute urban tree canopies have also been launched by the cities of Spokane, Olympia, Seattle, Tacoma (which has the lowest amount of tree canopy as a percentage of land cover in the Puget Sound Region), and Everett (just announced on July 31st!).

In Oregon, the Urban and Community Forestry Program has grown considerably in recent years, providing grant funding and technical assistance to cities and nonprofits working to expand their local tree canopies. The Portland Clean Energy Fund (PCEF) has committed to planting 15,000 trees on public and private property in neighborhoods lacking adequate shade over the next five years. And organizations like Friends of Trees have long supported area residents adding to their urban tree canopy.

Finally, the $1.5 billion dedicated to urban forestry in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has accelerated urban tree canopy efforts nationwide. Many—if not most—of these programs and organizations rely on volunteers to plant trees; dig in and learn more!

Need more immediate heat relief?

Planting trees and establishing green spaces are compelling long-term solutions to keeping our cities cool, but they take years to plan, build, and grow. For more immediate heat relief, several local, state, and federal grant and rebate programs exist to reduce the cost of a highly efficient electric heat pump (which, despite their name, provides both heating and cooling). Most electric utility companies also offer monthly bill discounts for low-income ratepayers.

Defend our Climate Commitments — Vote NO on I-2117

Clean energy. Public transit. Investments in frontline communities. And yes, abundant trees. Washington's Climate Commitment Act makes the state's biggest polluters pay for these community priorities while tamping down pollution.

However, an extreme right-wing mega-millionaire is trying to block our progress.

If Washington voters pass Initiative 2117, it would repeal our state's landmark law to cut pollution and erase billions of dollars in investments for our communities, while blocking future climate action.

Learn more about the No on 2117 campaign and stay tuned for upcoming opportunities to take action!