An unexpected climate catastrophe

Western North Carolina communities are working to recover from the worst weather disaster in the area’s history. Helene, a massive tropical cyclone supercharged by climate change, has left cities and remote rural areas devastated, with a rising death toll. As local residents focus entirely on caring for each other and trying to restore or regain access to the most basic necessities, the rest of the country is having to recalibrate our idea of what the frontlines of climate chaos look like: even communities far removed from vulnerable coastlines can wake up to hurricane floodwaters or other extreme weather events. Helene has now provided maybe the most dramatic demonstration so far that no regions are outside the risk zone for climate-fueled disasters.

Atlantic coastal towns like those on the opposite side of North Carolina are used to watching out for hurricanes every year, with annual cycles of stress and disaster preparedness. They're are also among the first places in the US that come to mind when thinking about the threat of climate impacts such as sea level rise and the intensification of tropical storms. Many low-lying communities have special reason to be on a first-name basis with particularly destructive storms remembered over the years: Rita, Camille. Andrew. Hugo. Irene. Sandy. Katrina. Maria.

By contrast, folks living far inland among the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee have had little particular cause to worry about climate disaster. In fact this area, especially the popular tourist destination of Asheville, NC, has famously enjoyed a reputation as a climate haven—sheltered from the weather extremes that scientists are increasingly linking to climate change.

That all changed last week as Helene, a category 4 hurricane with a diameter more than twice that of Katrina in 2005, made landfall in Florida and swept across Georgia, then western North Carolina. The storm dropped a colossal amount of rain, causing catastrophic flooding in Asheville and smaller mountain towns like Black Mountain, Swannanoa, Banner Elk and Boone.

These are places I know well, popular falltime gateways to the trailheads and state parks strung along the beautiful Blue Ridge Parkway. Growing up in Durham, North Carolina, I spent as many family vacation days in the mountains as on the more frequently storm-exposed beaches of the Outer Banks. I know many of the creeks and rivers that overflowed, and I have dozens of friends and family living in the area.

As initial reports on the storm came in last weekend, the scale of the damage became clear: massive flooding, with catastrophic damage to buildings, roads, bridges and other infrastructure. Close to a million people lost power and water across the region. Cell phone service was also knocked out, keeping many people from communicating with emergency services, or with friends or family in other parts of the country. Many people died in the floods—more than 100 in North Carolina alone; the total is expected to further increase as rescuers gain access to more of the affected communities.

Once the storm had passed over, and people began to figure out where power was on, what stores were open, where Internet access had not been cut off, a friend reached out from Asheville with this message: “On Friday night, my kids and I watched helplessly as the used oil from Precision Tune curled downstream in a foul-smelling black eddy. The roof of the Wendys was the only part of it showing above the waterline. The brewery on the corner was littered with washed up debris. Downed trees made walking difficult, driving impossible… I went out today to review the wreckage...and wish I hadn't. I am overwhelmed by a crippling sadness after seeing the devastation.”

Local officials in Asheville quickly began referring to Helene, without hyperbole, as “Buncombe County’s own Hurricane Katrina.” Central areas of some of the riverside and creekside towns were more or less erased by the flood. Houses and businesses were swept away in Chimney Rock and Swannanoa; flood waters swamped the streets of Black Mountain, Boone, Canton, Marshall, and entire districts of Asheville. Bridges collapsed, and many roads made impassable, including the major highway routes into and through the region.

The unprecedented scale of the disaster has left state and local officials unable in some cases to predict when essential services may be restored, although utility crews and other workers began cleanup efforts nearly immediately. The power outages meant food rotting food in grocery stores, gas stations unable to pump, and computers and televisions unable to provide emergency information. Sections of Interstate 40 may remain closed for months. In some cases local folks and relief workers are using donkeys and pack mules to deliver aid to communities cut off to vehicle traffic.

Leading climate activist and Asheville native Anna Jane Joyner reflected this week: “I’ve spent 20 years thinking about climate disasters, but I never imagined I'd be texting all my friends in Asheville with instructions on who to call for helicopter rescues.” Joyner’s Twitter feed right now comprises details about the storm’s damage, examples of resiliency as local communities begin to recover, and above all, her sense of urgency to confront the main cause of global warming that’s making storms more dangerous and placing more communities at risk. “My hometown and whole region were just destroyed by climate change aka the fossil industry.”

What Helene is telling us about storms of the future

Hurricanes are an annual possibility for people living in coastal areas of the southeast. Predicting how active or how destructive a hurricane season will be is very tricky; storms are influenced by a complex range of atmospheric and oceanic factors. But storm trackers have noted that, overall, storms seem to be trending towards greater severity.

While exercising caution about attributing specific causes for events as organic and literally wild as tropical cyclones, climate and weather scientists have long agreed that climate change likely makes such storms worse. “A hotter ocean will allow hurricanes to grow more powerful,” explains hurricane scientist Jeff Masters. “Climate change makes the strongest hurricanes stronger, increases rainfall, increases storm surge damage through sea level rise, and increases the probability of rapid intensification events.”

One noteworthy aspect of Helene news coverage has been journalists’ immediate readiness to name the fact that global warming is a key factor contributing to the storm’s severity. Lavana Ramanathan and Umair Irfan describe Helene as a wakeup call: “it’s impossible to look at hurricanes in 2024 without also considering the context of climate change, which has made everything from rains to drought to wildfires more extreme globally, and put more ecosystems and humans in danger in the process.”

As noted above, Helene shows that no regions are outside the risk zone for climate disasters. We’ve gotten this message before, with wildfires, drought and desertification affecting more western communities, and weather extremes becoming more common across the country. Will the growing realization that we all live in the shadow of climate chaos increase our sense of urgency to enact real solutions, by speeding up our transition away from fossil fuels?

Disaster compassion is real

Before hitting western North Carolina, east Tennessee, and Virginia, Helene brought record-breaking storm surges to the Florida Gulf Coast, also wreaking havoc in Georgia and South Carolina. Many communities in the region, including Augusta, GA, are experiencing similar devastation, and have similarly urgent needs. And outside the US, region after region is experiencing catastrophic flooding, including Guerrero, Nepal, The Philippines, India, central Europe, Southeast Asia, North Africa, and many other places. Experts have linked these extreme weather events to climate change.

In North Carolina, local, state and federal officials have begun what will be the protracted and expensive work towards recovery, even as the extent of the damage has yet to be fully grasped. And local people have begun helping each other, in what NC-based author and musician Margaret Killjoy called “absolutely classic disaster compassion… mutual aid groups are working nonstop” to transport supplies from Asheville to residents of more rural, isolated communities.

Want to help relief efforts? Here are some organizations providing different types of assistance:

- United Way of NC

- Mutual Aid Disaster Relief

- Beloved Asheville

- American Red Cross

- Mutual aid evacuees support fund

- Mountain True

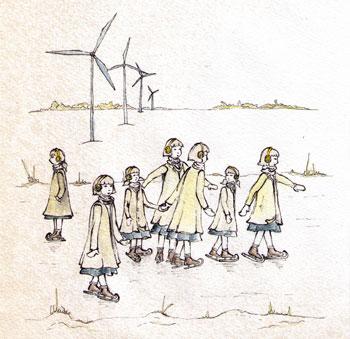

Image: “Rhythm,” by Asheville-based artist Jessica White. I bought prints of Jessica’s work several years ago at her studio in the River Arts District—a neighborhood of gallery spaces housing dozens of painters, potters, jewelry makers and other artists, alongside cafe and brewery spaces. During Helene, the entire district flooded and was destroyed.